Does pedagogy constrain children’s desire to explore?

Guided or didactic teaching, which can be considered a natural educational situation, allows for the efficient and rapid transfer of knowledge. However, previous research has pointed out that this method, although it efficiently transfers knowledge, can constrain the exploration and discovery of hidden causal relationships in the external world. For this reason, some experts argue that learning in a pedagogical context and individual exploration are mutually exclusive learning processes. It is possible that pedagogy limits the autonomous acquisition of information and the autonomous search for alternative possibilities.

However, research on children’s exploratory learning has shown that in some situations, pedagogical cues may actually facilitate independent information seeking. These situations, which the literature refers to as guided discovery, are characterised by children being given the opportunity to seek information on their own, and adults merely reinforce the “correct” knowledge or behaviour produced by the children and help them when they get stuck. Therefore, learning through pedagogical cues and independent learning may not necessarily be in conflict but can complement each other.

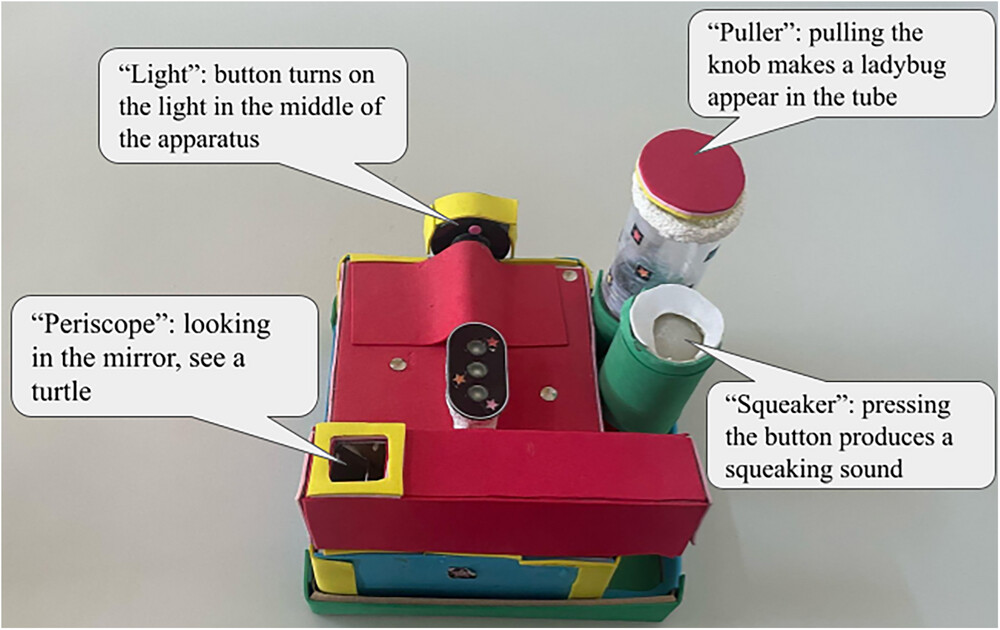

To investigate this, Rebeka Anna Zsoldos and Ildikó Király designed a special multifunctional object for preschool children. During the research, the children experienced one of the functions of the toy in different ways. Children in the first situation were introduced to the toy in a guided, pedagogical way, while in another situation children discovered the function themselves. In both cases, adults gave the children the same instructions about the function. In addition, another group of children were also introduced to the toy either through demonstration or discovery, but here the adult’s communication was not pedagogical, i.e. it did not include specific information on the operation of the toy. The researchers wanted to know how long the children played with the function they first learned about, and how much they looked for alternative possibilities in the object.

The results showed that, in both cases, the pedagogical cues drew attention to the importance of the function learned first: children played with it for longer than in the other cases where they had not received teacher guidance. The research also showed that if the use of the toy is not demonstrated to the children but it is left to them to independently find out how it works, the pedagogical cues do not inhibit later exploratory behaviour.

These results suggest that pedagogical cues and learning through exploration are complementary: pedagogical cues highlight important information from the context, while exploratory behaviour allows children to acquire additional, complementary knowledge. Autonomous learning contributes to the development of a richer body of knowledge and to the exploration of new possibilities, while information from peers can serve as a starting point for autonomous learning since children do not have to reinvent already known pieces of evidence. In this way, the two forms of learning support, rather than oppose, each other in deepening children’s understanding of the world.

The full study is available here.