People won’t quit smoking if they are warned of long-term risks only

Our willingness to quit smoking is greatly affected by how far into the future we think the negative effects of smoking and the positive effects of quitting will manifest themselves, argues a study conducted by researchers of ELTE PPK that involved 1500 smokers.

Smoking is a serious public health concern throughout the world: it is the leading cause of diseases and death that could be prevented. Although science has supplied significant amounts of proof regarding the harmful effects of smoking, the prevalence of tobacco addiction has not decreased in the last few decades.

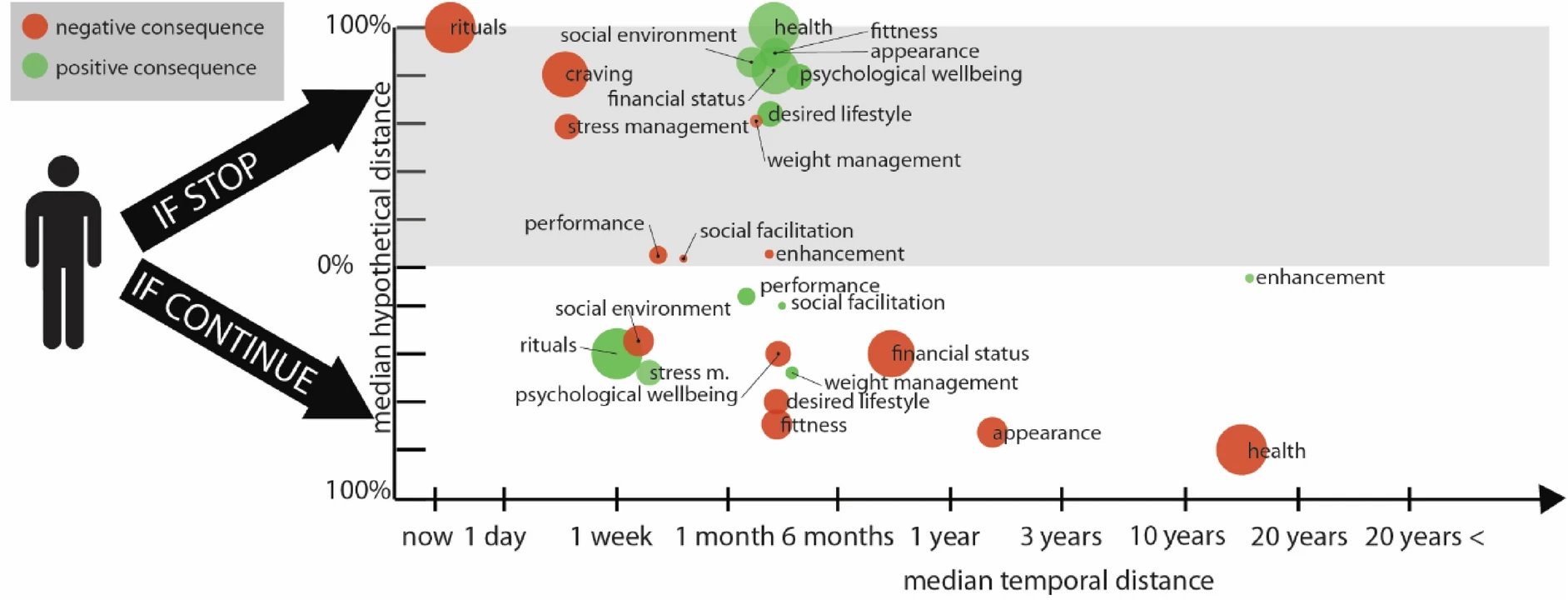

In their study, members of the Addiction Research Group at ELTE PPK – Domonkos File, Beáta Bőthe and Zsolt Demetrovics – examined how the willingness to quit smoking correlates to psychological distances. The term ‘psychological distance’ refers to the perceived subjective, emotional and cognitive distance between the present and a future event. The larger this perceived distance is, the lower the intensity of our emotional reaction; in other words,

it is less likely that a perceived distant event will cause a change in our present behaviour.

This may help us better understand why it is a difficult task to quit an addiction: the negative effects on health can be noticed in the far future only (e.g. a higher risk of lung cancer), whereas the bothersome side effects of quitting appear almost instantly (e.g. craving for a cigarette). People tend to attach minimal significance to future events, which is especially true for smokers, meaning that they usually ignore completely the delayed damage to their health.

Visualising psychological distances with regard to the positive and negative consequences of both smoking and quitting.

Another important thing to note in connection with smoking is that it does not only affect physical health. Addiction can cause harm in other areas of life as well, such as in one’s financial situation, psychological well-being, fitness or appearance.

In their survey-based study that involved nearly 1500 smokers, the researchers found that if the negative effects of smoking and the positive effects of quitting were close in time to the respondents, they judged it more likely that these consequences will actually happen. This led to a stronger willingness to quit smoking. An important result of the study is that although the subjects perceived the health damages as distant, they associated other drawbacks, such as the loss of fitness, with immediate negative consequences.

The results of the study raise crucial questions regarding the efficiency of the current communicational campaign against smoking. Most messages that urge people to quit smoking carry a threatening tone and focus on health issues – cue the frightening pictures on the cigarette packs. This method, however, often triggers a stress reaction, which inhibits the cognitive processing of the message. Another factor that decreases the efficiency of the communication is getting overly familiar with the message by encountering the same argument every time (e.g. that smoking causes lung cancer).

But how could the anti-smoking communication be improved? According to the researchers,

it would be more useful to focus on the advantages that come with quitting, such as the overall feeling of well-being or the improved appearance.

These would trigger positive reactions in the recipients instead of fear and anxiety. Besides, the perceived psychological distance of the beneficial consequences of quitting is significantly shorter than that of the harmful effects of smoking: the former is judged to be around 3-6 months, while the latter falls somewhere between 11 and 20 years. Humans perceive long-term consequences in a more abstract manner, which leads to less specific and definite solutions (“I need to quit smoking”). In contrast, short-term effects are perceived more concretely, and therefore our steps towards reaching our goals are more immediate and focused (“To be able to quit smoking, I need to master techniques that help me overcoming cravings”).

Since the health risks posed by smoking are typically long-term, it would be worth expanding the communication to include a range of other potential consequences as well. In this way, the researchers argue, these messages could become more efficient in urging smokers to quit their addiction.

The study conducted by the researchers of PPK can be read in the Scientific Report.